Interview: Blaze Ward on “Pulp Speed for Professional Writers”

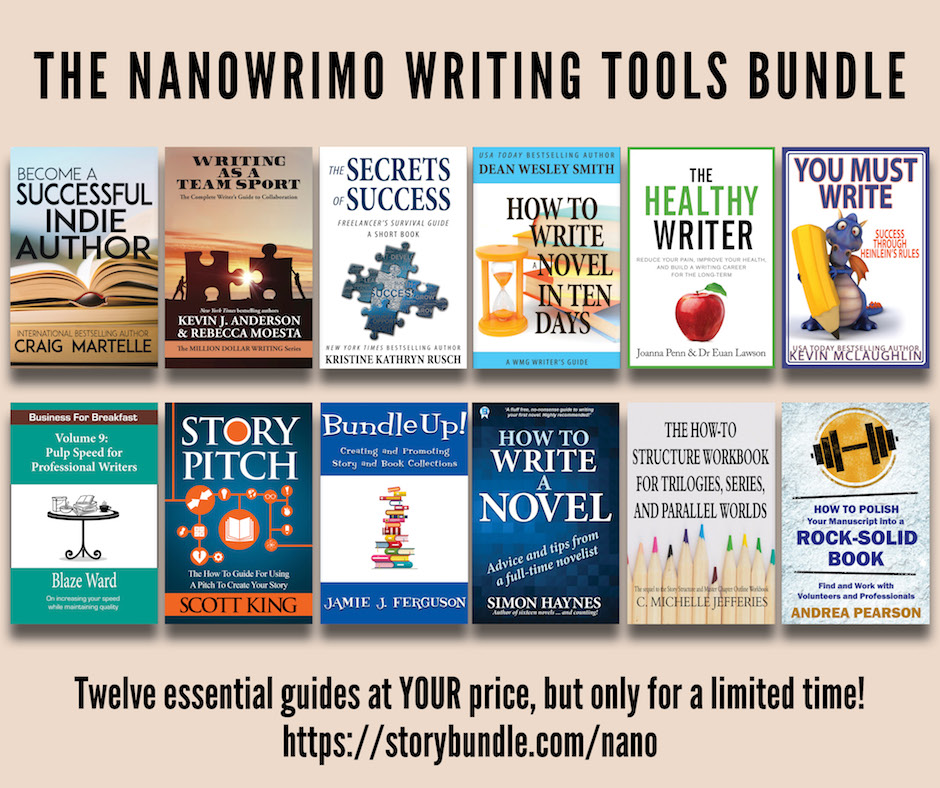

Pulp Speed for Professional Writers is in the NaNoWriMo Writing Tools bundle, a collection of a dozen books on writing. A portion of the proceeds goes directly to the Challenger Center for Space Science Education, a non-profit group created by the families of the crew of the Challenger shuttle. This bundle is only available through the end of November 2018.

Pulp Speed for Professional Writers is in the NaNoWriMo Writing Tools bundle, a collection of a dozen books on writing. A portion of the proceeds goes directly to the Challenger Center for Space Science Education, a non-profit group created by the families of the crew of the Challenger shuttle. This bundle is only available through the end of November 2018.

Meet Blaze!

Blaze writes science fiction and fantasy. In addition to his own short stories and novels, he’s the editor of Boundary Shock Quarterly, a speculative fiction magazine with the motto “On theme. With weird.” He also writes non-fiction books for writers. Blaze writes very, very fast!

Pulp Speed for Professional Writers

They’ve told you that writing fast is impossible. They were wrong.

You too can create stories at the speed of the great pulp writers. Not only that, but your craft will actually get better the faster you go. It just takes time and practice.

Come learn the things I discovered as I went from writing at mundane rates to Pulp Speed.

Topics include:

- Where did the term “Pulp Speed” come from?

- What are the classifications of Pulp Speed?

- How does your health and ergonomics impact your speed?

- What is possible?

Are you ready to break loose and start turning out good stories at amazing speeds? Do you have what it takes to go “All Ahead Crazy?”

Excerpt

We should start off by talking about this thing called Pulp Speed. This is another term for Really Freaking Fast. To understand the background, we need to go back to the era of the pulp writers, which is generally from the end of the First World War, give or take, up until perhaps the end of the Fifties. So about a long generation of time.

In those days, there were not a lot of books published in the field we know today as science fiction. The modern paperback novel, as we know it, came about after World War Two, as a result of all the books that the US Government printed for soldiers during the war. That taught an entire generation of men (and women) to read for pleasure.

Before that, what you had were the magazines. Things like Amazing Stories, Worlds of Wonder, The Black Mask, Weird Tales, etc. They came and went frequently, with a only few of them surviving long, and fewer have made it clear down even to the present. Each tended to lock into a particular genre, and then tried to generate enough newsstand sales to get a subscription base going that could keep the magazine solvent. It didn’t always succeed.

For such magazines, they frequently paid a penny a word (US $) for stories in science fiction. Assuming a short story came in at 5,000 words, the story would earn the author $50. For comparison sake, the median US income in 1940 was $956, or roughly $80/month. Mind you, this is median, so just selling a single story in a month would get you a nice, lower-middle-class lifestyle. And if you sold two, you were living high on the hog.

Not every story would sell, but if you hit once or twice per month, you were set. The key was to write a lot of stories, and send them off. Every story we write is not Pulitzer material. And spending a whole month crafting such a story is no guarantee that it will be any better than one you wrote in an afternoon.

Furthermore, a lot of writers were submitting in those days, and some of them just weren’t that good at their craft. The editors had their favorites, people they could rely on to produce good enough work, on theme, on a regular basis, so they could, it turn, fill a whole magazine. But you couldn’t publish three stories by Bob Brown in the same magazine this month.

You could, however, publish three stories written by Bob Brown, and use pennames on two of them, so “Marc Jones” and “Stan Woods” could also have stories here.

What we had was an ecosystem that favored good writers who could produce good words at speed. They wrote a lot of words. Whole acres of them. Because they treated it like a job.

What does that mean?

These days, you generally go to work and are in an office or in front of a press for eight hours, with a break for lunch and smokes.

The Pulp writers sat down and typed for eight hours.

The new writer, just sitting down and figuring out her craft (and typing on a keyboard, rather than longhanding), will quickly get up to a pace of about 500 words per hour. However, she won’t be able to write for eight hours straight.

Writing for that many hours is a skill, as well as a muscle. Treat your writing the same way you would train to run a marathon. Start slow and careful, and slowly push yourself to greater lengths and speeds, rather than trying to do it all at once.

– from Pulp Speed for Professional Writers by Blaze Ward

The Interview

What is “pulp speed,” and where did the term come from?

Pulp Speed One is defined as One Million Words Per Year, or about 84,000/month. It dates back to the Pulp Writers (1920-1960 more or less) who generated an amazing number of short stories each month and sent them off to all the pulp magazines of the day.

Can anyone learn to write at pulp speed?

You can. It is a muscle, just like any other. True Pulp probably requires that you have a supportive enough spouse that you don’t have a day job any more. I was writing 450,000/yr with a full time job and a long commute. Once I had the time to think. I more than doubled my speed in about three months, and I have held at 100,000 words per month for six months now, with no slacking of pace.

Does this work better for different types of fiction, or different lengths of stories?

I write Science Fiction primarily. Dean Wesley Smith writes all over the map. I find it works better for longer pieces, because then you don’t have to spend as much time on administrative overhead (covers, blurbs, formatting, etc.) I also like to write short novels (40-50k) because then I’m in a different universe and different characters every two weeks, so it keeps me from dreading opening a file that turns into a doorstop monolith.

How do Heinlein’s Rules for Writers help writers get to pulp speed?

- You must write.

- You must finish what you write.

- You must refrain from rewriting, except to editorial order.

- You must put the work on the market.

- You must keep the work on the market until it is sold.

Quoted more or less above. I have a different mantra I use for writing, because I’m almost completely indie, so 4 & 5 have different meanings for me. “Sit down. Shut up. Write.”

It has to be interesting enough that you wake up in the morning and say to yourself “Oh My God I get to go make shit up for a living!!!” I cycle while I write and have taught myself to write clean first drafts, so I make a single pass after I’m done and send it to my First Reader.

Don’t rewrite. Don’t redraft. Time you spend writing your novel again is time I’m writing a second (and more) novel. Once it is done, I put it out for publication and go on to the next one. I won’t win awards for pretty words, but I make a living from my writing and most of those award winners don’t.

What inspired you to write Awaken the Star Dragon, and how does Fermi’s Paradox tie in with this?

What inspired you to write Awaken the Star Dragon, and how does Fermi’s Paradox tie in with this?

Fermi’s Paradox: Where is everyone?

Jeffries Corollary: We are the most dangerous, psychotic species in the galaxy and they’re hiding from us.

What happens when a crime boss out there decides to abduct a criminal here? The good guys decide they have to recruit a cop.

I write a lot of so-called military SF, and grand space opera. I wanted to write something that was Pulp in feel. I envision my writer voice as standing in 1950, with the state of culture and technology then, and trying to envision the world as they would have, rather than as a modern prognosticator would. It gets silly.

Boundary Shock Quarterly is a speculative fiction magazine you started in 2018. What inspired you to start this magazine, and what are you enjoying about it?

I have always wanted to do something like this, but your choices were to either do a crowd-funding thing (Kickstarter, Indigogo, etc.) or run up a massive debt on your credit cards that probably never paid off. But the Seventh Indie Revolution in publishing has finally made the tools available to anyone with enough gumption. I wrote down every one of my steps because once I got there, I wanted others to be able to replicate it (See below) and challenge the major genre magazines. There are quality writers out there, just waiting their chance.

In addition to creating Boundary Shock Quarterly, you’ve written a book about the process: How to Launch a Magazine for Professional Publishers. What’s the biggest lesson you learned from creating this magazine?

That it was possible. That anyone could do it, if they wanted it bad enough to step up. My Syndicate has been a bit like herding goldfish from time to time (cats don’t move in three dimensions) but they’ve also come through with some quality stories that made it fun.

What have you found most interesting about the complex world-building you’ve done for your science fiction series Alexandria Station?

Inventing a Cavalry (men and women on horses = Hussar) Legion and invading a planet with it. And building outward from several hundred pages of extended universe bible about details and people. I can’t be wrong with my technology, generally because I never explain how it works. I can only be inconsistent.

What’s your most important piece of advice for authors who want to achieve pulp speed?

See above. “Sit down. Shut up. Write.”

Pulp speed is a factor of how many hours you spend at the keyboard generating words. And you must find the desire to do this. You must want this more than other things.

I sold my last television four years ago, and I don’t “watch shows.” Those are hours I spend possibly goofing off, but more likely working on story and world-building.

What’s your current pulp speed, and what do you expect is your personal max?

Currently, I have been holding at Pulp Two (100,000+/month) as a marathon pace. My personal best was Pulp Five (150,000/month) pace, except I intentionally took the last three days of the month off to hold it under that. But it is a muscle and I am writing faster now than I did even two months ago, so I might try pushing at some point, just to see.

What story (or stories) are you working on now, and what’s fun about what you’re writing?

I got a request to be in a bundle, with the curator sure I had novels he hadn’t seen. But all I have left in the genre were Book Twos+ (the Ones were already in bundles). But I offered to write something on short notice, as I was just finishing a novel that day, and needing a project to start (the writing schedule is always in pencil).

So I’m generating a new Handsome Rob novel (in the Alexandria Station universe) and it has to be done in two weeks. 🙂

About Blaze

Blaze Ward writes science fiction in the Alexandria Station universe as well as The Collective. He also writes fantasy stories with several characters and series, from an alternate Rome to epic high fantasy in the desert.

Blaze’s works are available as ebooks, paper, and audio, and can be found at a variety of online vendors. His newsletter comes out quarterly, and you can also follow his blog on his website. He really enjoys interacting with fans, and looks forward to any and all questions—even ones about his books!